Speculative sampling: LLMs writing a lot faster using other LLMs

Behind the beautiful name of Speculative sampling lies a neat technique to have a large language model generate tokens up to three times faster 🔥 The technique has been developed by various research teams, including one from Google DeepMind who published it here.

See for yourself:

And also try it yourself on this repo, containing a bit of code Dust released to illustrate the technique.

What is it?

The basic hypothesis behind this, which turns out to be true, stems from this idea: "If humans can create content faster using large language models, maybe LLMs too can write faster using smaller language models".

To illustrate, you can write blog posts with chatGPT a lot faster, as everybody knows, e.g. with the following process:

- feed chatGPT with the title and first line;

- have it generate a few next sentences;

- if they're good, generate some more, until they start being bad;

- rewrite the last generated parts to put chatGPT back on track;

- iterate the process.

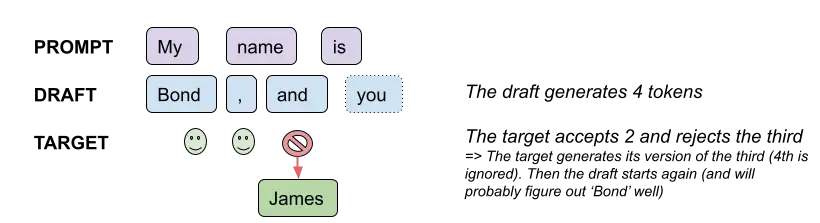

Well, an LLM can do the exact same, using a smaller model as its own mini-chatGPT, at the token level: have a small model, called a draft model, generate a few tokens, until it decides the draft model is really wrong, then generate the next token itself, then have the draft model generate again, and repeat. The larger model is usually called target model.

Generation quality

What is impressive is that this can be done without loss of quality. Just as a writer using chatGPT is still expected to produce at a quality level at least as good as they would deliver without an AI, Speculative Sampling would not be worth it if it reduced quality.

But it can be shown that the quality of Speculative Sampling (SSp) is the same as regular sampling (RSp) in two ways:

- theoretically: the token probability distribution is proven to be the same as in the DeepMind paper;

- empirically: by using benchmarks and observing that both perform exactly the same. In the Dust repo we shared, we make Llama models perform a few thousand of multiplications and we show that the success ratio are the same; the Deepmind paper also performs similar empirical tests on other benchmarks (note: in our case, it also confirms our implementation is correct 😉)

How and why it works

Let us provide a simplified explanation of how SSp works (optimized for clarity over precision 😉—see the DeepMind paper for full details)

Small models are significantly faster than large ones—e.g. the tests in the repo show the Llama 7B model is ~8 times faster than the 65B.

The major observation behind SSp is that it takes the same time for a target model to generate a single token, than to check how likely it would have generated a sequence of e.g. 4 tokens.

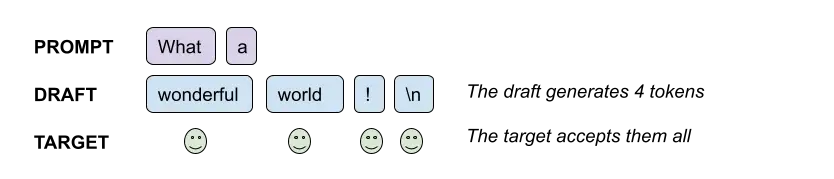

Therefore, having the draft model generate 4 tokens, and then the target model check they are good, can be done in roughly the same time as sampling a single token from the target model. This is what SSp does: sample 4 tokens for the draft (4 is a hyperparameter here), assess how good they are sequentially and accept them until one is too bad, then sample a token it would have generated itself—at no additional cost, because the "likeliness check" of the target gives us token probabilities we can sample directly from, without another forward pass.

If the draft model is often correct, i.e. the tokens it generates are validated by the target model most of the time, then the gain can be significant. On dumb cases such as completing the prompt "1 2 1 2 1 2 1 2 " etc. you can expect all tokens to be accepted all the time, so you'd get a roughly 4x speed up.

Of course, in real settings, the draft is sometimes wrong, but less than we would expect since in many, many cases at least a few tokens are obvious even for a small model, e.g.:

- "How are you" -> do, ing, ?, \n — 4 obvious tokens (remembering tokens are not words)

- "It was amaz" -> ing, !, \n — 3 obvious tokens

Generic examples include punctuation, capitalization, language idioms, etc.

The quality remains the same thanks to the Modified Rejection Sampling scheme, as the DeepMind paper's author call it. The decision to accept a draft token is made stochastically depending on the ratio of probabilities of this token (target over draft), and on failure the next token is resampled according to adjusted probabilities. This scheme allows to recover the target model's probability distribution (as proved in the paper's appendix).

Note: speculative sampling has also been discovered and explored by other teams, with other names, e.g. assisted generation at HuggingFace, or Blockwise Parallel Decoding at Google Brain.

🙏 to the open ecosystem

Anybody can use this sampling strategy, as we hope the repo shows. It was made possible by the openness of the ecosystem:

- openly accessible research from Google DeepMind;

- open source software from HuggingFace;

- open source model weights (kinda) from Meta's Llama.

BTW, if we were to learn that OpenAI's chatGPT has used an equivalent of SSp for a while, it wouldn't come as a surprise.

The fact that it is now usable by all LLM workers shows the value brought by the community's openness. It follows a growing trend visible in recent developments in the field : Llama then Falcon (accessible model weights), Chinchilla (optimal training of smaller models), LoRA (incremental training), etc.: Faster, smaller, more efficient, more trainable models are increasingly being made available to all. It's a huge innovation enabler.

Next steps

The repo we shared was based on Meta's Llama models using HuggingFace Transformers. Experiments on newer models—e.g. the recently released Falcon—, faster parallelization code—e.g. using Meta's fairscale lib—and hyperparameter tuning—e.g. optimal number of draft tokens—are on the radar.

Apart from speculative sampling, great new techniques are emerging that can help us build. Non-exhaustive list 📜

- QLoRA: applying LoRA to quantized models for even more accessible LLMs hardware-wise;

- Tree-of-Thought: generalizing Chain-of-thought, to make existing models stronger at problem-solving;

- RLAIF strategies so that anybody can afford specializing models—since it removes the need to hire click workers.

Lots of interesting paths to innovate. Crucially, it's essential to find ways to ground the models in truth, ensuring the factuality of their outputs and minimizing potential hallucinations while we forge those paths towards better LLMs. At Dust we look forward to experimenting on those to further build tools that make teams smarter.